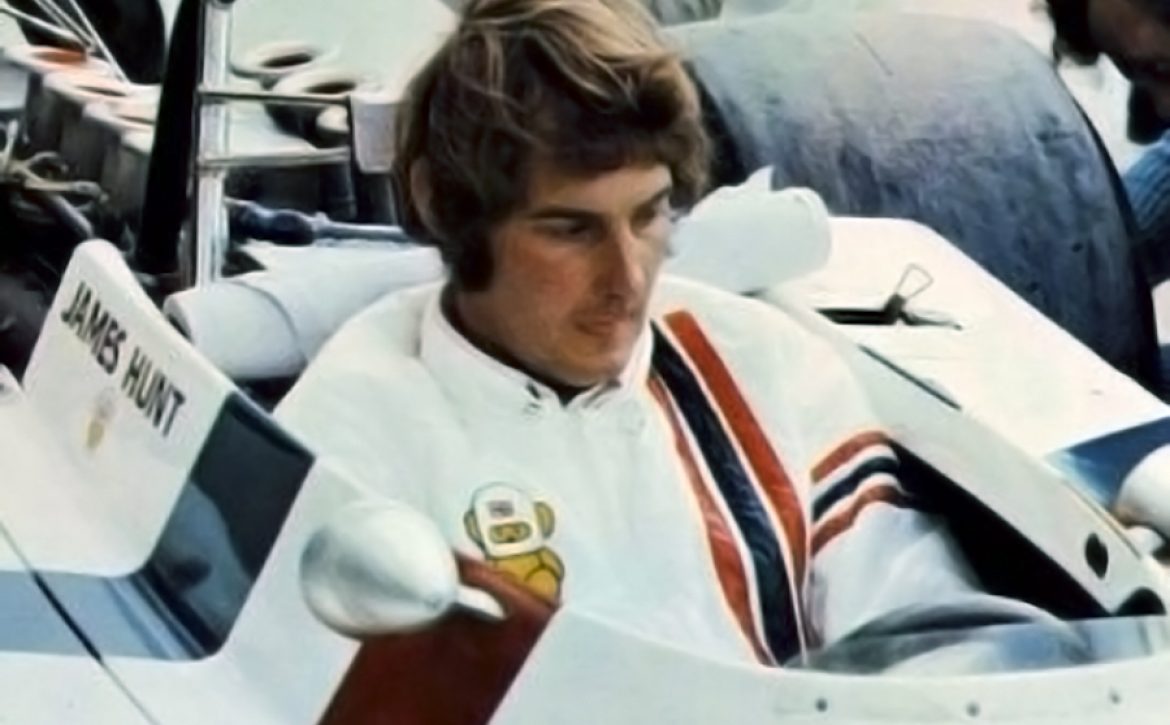

Sex, drugs and fast cars: The legend of James Hunt has set Hollywood hearts racing

Even if you have not the faintest interest in motorsport, or Formula One – that shiny Babylon of sponsors and sleaze – the lure of James Hunt is hard to resist. Handsome, brave, articulate, he had a reputation for living as fast off the track as on.

He may have been said to have slept with 5,000 women and had the words “Sex, breakfast of champions” sewn on to his overalls, but for all the gloss and glamour, there was another side to Hunt. He was a nervous driver, who vomited before every race. He was a sensitive animal-lover, who reared budgerigars, and banned hunting on his Buckinghamshire farm. A series of financial blunders meant that, later in life, he was reduced to an Austin A35 van, or a bicycle, on which he’d be spotted pootling round Wimbledon.

Now, a month ahead of the 20th anniversary of Hunt’s death of a heart attack, aged just 45, there is concern among friends that the racing driver’s complexity could be forgotten. Lord Hesketh is among them. “James was a fantastically good sports person and an immensely civilised guy,” he says. “I won’t be seeing the film. I hope that I am wrong, but one of the things about people who makes films is that they’re not interested in being truthful.”

In 1972, as a rich 22-year-old, Alexander Hesketh had launched his own racing team, and later gave Hunt his break into Formula One. “The thing you’ve got to remember is that all the other teams were run by people 20 or 30 years older than us. When he came to me, he was 24 and I was 22. We were all very young, none of us were married, and everyone else was middle-aged. So inevitably people said how wild we were.”

But how accurate is the image of Hunt as a playboy?

Max Mosley, a former president of F1 governing body the Fédération International de l’Automobile and co- founder of the March racing team in 1969, says Hunt was a bon viveur. “Yes, he was totally wild, but I never knew him to do anything ungentlemanly.

In 1976, Hunt was crowned world champion but retired from the sport after the 1979 season, aged just 31. Why did he bow out so young? “I remember him saying,” says Mosley, “that driving at those sorts of speeds, if you’re racing for the lead, or racing for the world championship, is fine. But if you’re in 14th place, you suddenly start thinking, is this sensible? It was very dangerous in those days. Everyone always said you could have a nice party with all the people who got killed. It was appalling.”

Hunt’s choice of career was not obvious from his childhood. Born to a stockbroker father in Surrey in 1947, one of six, he was a bumptious and single-minded child, who thrived at prep school and Wellington College. Although not academically rigorous, he was a proficient trumpeter, and excelled in all sports, especially tennis and squash. As a sensitive child, he connected with animals, particularly dogs and birds. And apart from playing on his Scalextric set, he showed little interest in cars. But a chance invitation to a race meet at the Snetterton circuit in Norfolk the day before his 18th birthday got him hooked on racing. “It was instant commitment,” he later recalled. “Motor racing was something impossibly remote… but here was something within reach of a mere mortal.”

He shelved his plans to become a doctor and began saving money to go club racing. His parents were less than enthused, especially when Hunt proposed a deal: they had been prepared to spend about £5,000 sending him to medical school; instead, he suggested they gave him £2,500 to buy his first car. The answer was a polite no.

However, his determination to race paid off, and Mosley recalls the first time he saw him was at a race meet at Snetterton in 1969. “There was a Formula Ford car that seemed to be going far too fast. And later in the paddock I saw this tall figure get out of it, and that was James. He didn’t have any proper racing clothes, but he just had this great natural talent.”

Lord Hesketh was also struck. “He was very quick. He wasn’t fearless – he was well aware of the danger. If I look at that period, most of the people I knew – Piers Courage, Ronnie Peterson – got killed. It’s not that like that any more.”

A good example of Hunt’s skill was his performance at Silverstone. “For me, the greatest corner in Grand Prix racing was Woodcote at Silverstone,” says Hesketh. “The camber changes, and you can’t see the exit of a very difficult corner. It doesn’t exist any more. And if anything tells the truth, it’s the stopwatch. We always said that Woodcote was worth one second in a lap to us, because James always took it flat [out]. When he won his first race, he overtook Ronnie Peterson, who was in the lead, with two wheels on the grass on the inside. When you’re doing 165mph, that takes some doing.”

Yet Hunt’s early years in racing, before he was signed to Hesketh Racing, were dogged by lack of funds and some unfortunate accidents. On one occasion, at Oulton Park, he lost control and was catapulted into a lake. The car was ruined, and had been bought with a loan, which he had to spend the next two years paying off. Hunt later said he would probably have been killed had he been strapped in. “Seatbelts were not yet compulsory and I didn’t have them because I couldn’t afford them,” he recalled. “Had I been wearing one, I might have drowned.”

A popular anecdote is that he would have sex minutes before a race. (Patrick Head, co-founder of the Williams team, claims he walked in on Hunt with his overalls round his ankles, cavorting with a Japanese girl, in a pit garage, moments before the start of the crucial Mount Fuji Grand Prix.) And there was also that ritual of being sick, though he denied it was from fear of death. “I was sick with tremendous nerve pressure,” he said. “But that was basically because I was driving my own car, and if I crunched it, I was out of money and there was no way I could repair the car. So it was fear of my future on the financial side and on the job-security side. Nothing to do with danger.”

By the time he was in Formula Three, he had earnt the nickname “Hunt the Shunt”, which Max Mosley inadvertently coined. “He didn’t shunt more than anyone else, it just happened to rhyme.” Hunt was also a dream interviewee for journalists. “We had him in the works Formula Three team [one owned by the manufacturer, rather than a private entry] in 1972, and the car was no good,” says Mosley. “And then he told the press the car was no good. It was absolutely true, but I didn’t think that’s what you did if you were a works driver.”

Formula One in the 1960s and 1970s was, however, still a sport for amateur gentlemen rather than close-lipped pros. “The world was a very different place,” says Hesketh. “There wasn’t a great deal of money about. And our budget was less than anybody else’s. For our first season we had just one chassis and two gearboxes. It cost about £50,000 – about £500,000 now. Today, that would just about pay your PR man.”

Hunt left Hesketh Racing after the 1975 season, and joined McLaren, which was a much better-funded team. “I couldn’t afford to go on,” says Hesketh. “And I wasn’t going to ruin his career by keeping him in an uncompetitive car.” Before 1976, Hunt had only won two Formula One races, and racing for Hesketh, he came fourth in the world championship on 33 points, to Lauda’s 64.5.

ll that immediately changed when he began racing with McLaren the following year. He won the first two races of the year, which were non-championship events, and then won six out of 16 Grand Prix races. One of these was the infamous German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, when Lauda crashed in the first lap, and suffered appalling burns after being trapped in his car. (There were 38 track fatalities in the 25 years between 1953 and 1978.)

Despite falling into a coma, amazingly, Lauda was back at the wheel only six weeks later, and finished an impressive fourth at the Italian Grand Prix at Monza. Hunt made gains on Lauda’s lead in the points table during his absence, winning at the Canadian Grand Prix, and the US East GP, the penultimate of the season. Scheckter recalls the tension of that period. “It was at Watkins Glen [in New York], and [Hunt] was behind me, and caught me up. I could have held him back, but I didn’t. I felt that I wasn’t going for the championship, but I always had respect for those that were.” By the time of the Japanese Grand Prix, the last race of the season, Hunt was only three points behind Lauda.

On the day, there was torrential rain, and after two laps Lauda retired, saying it was too dangerous to carry on. Hunt did, and finished third, winning the championship by just one point. It was the most riveting climax to a Formula One season ever, and the world had Hunt-mania. Though he raced with McLaren for two more seasons, he never again achieved that record, and came fifth and 13th in the world championships of 1977 and 1978 respectively.

After Formula One, Hunt initially maintained the lifestyle, but without the adrenalin and glory that his racing had brought him. He bought a villa in Spain and a farm in Buckinghamshire, and divided his time between them, as well as a mews house in west London. Jody Scheckter lived nearby in Spain, and recalls that Hunt didn’t sit comfortably with the ex-pat lifestyle. “There wasn’t much to do; it wasn’t really for him.”

Hunt opened a nightclub, Oscar’s, named after his German Shepherd, and in 1982 met Sarah Lomax, an interior decorator who was on holiday with friends. They married, moved to Wimbledon, and had two sons. (The marriage fell apart in 1989, though they remained on good terms. His previous marriage, to model Suzy Miller, had lasted only 16 months, and ended early in 1976, when she left him for the actor Richard Burton.)

Hunt’s career in broadcasting went surprisingly well, despite Murray Walker’s suspicions on hearing he was being joined in the commentary box. “James Hunt was, in my eyes, the archetypal loud-mouthed, irresponsible Hooray Henry,” he said. “My immediate reaction was a mixture of concern and irritation. I wondered if the BBC was trying to ease me out of my job. I had been doing it alone for two years and I didn’t want somebody else horning in. Particularly some bloody Grand Prix driver who knew nothing about commentating, and particularly James Hunt.”

In the event, it was a great success, despite their different styles. According to Hunt’s biographer, Gerald Donaldson, at his first Grand Prix in Monaco in 1980, Walker was infuriated that Hunt turned up minutes before broadcast, shoeless and with his leg in plaster. “He planted the injured limb in Murray’s lap and proceeded to consume two bottles of rosé during the broadcast.”

Hunt later turned his attention to writing, and wrote a Formula One column in The Independent during the 1991 season. His first piece was typically forthright. “We are supposed to be showing the rest of the world the way in motoring matters and it is high time Fisa’s rules permitted only environmentally friendly fuel,” he wrote. Hunt was also a vocal advocate of improved safety, which did eventually come to the sport.

The ultimate irony was that a man who risked his life so often on the track should lose it in the safety of his home. He died in the early hours of 15 June 1993, from a massive heart attack. Earlier that day, he had proposed to his girlfriend, Helen Dyson. Towards the end of his life, he had given up drinking and smoking, thanks largely to her. He was beginning to get fit again, and had taken up cycling.

“He was famous for living life to the full,” Dyson said after his death. “But I knew a much quieter man. He was a wonderful father to his sons, and my best friend.” Still, he didn’t mind being remembered for his wild side. To make sure everyone had a good time, he put £5,000 towards the wake of his own funeral. By all accounts, it was quite a party.